SHILLONG:

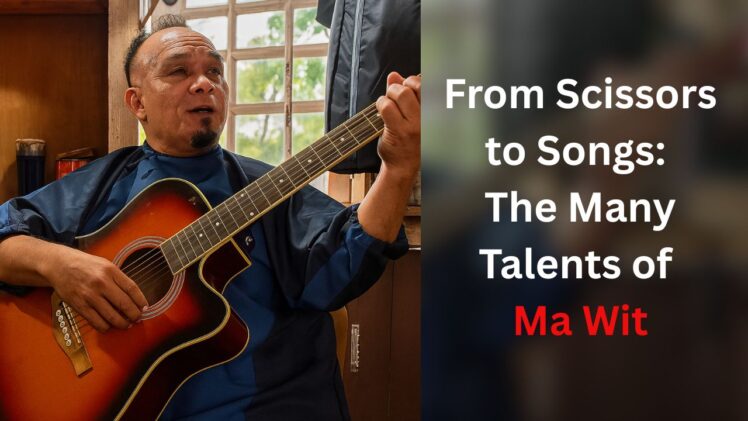

In the heart of Mawlai Umthlong lives a man whose spirit shines brighter than any challenge he faces. Known affectionately throughout the locality as Ma Wit, his real name is Aiborlang Lemnong. The nickname, a playful mispronunciation of “Bahrit” (meaning ‘small’ or ‘younger brother’) by his younger sibling became used by his family and eventually by the close-knit community that surrounds him.

Ma Wit is no ordinary man. Despite being unable to walk since childhood, a disability that might deter many, he has cultivated a life of remarkable independence and purpose. He runs a small barber shop, where he skillfully wields scissors and combs, transforming his clients’ looks with a practiced hand. But his talents do not stop there. He is also the go-to person in the village for repairing damaged electrical appliances, be it a rice cooker, an iron, or a grinder, Ma Wit finds a way to fix them.

Beyond his practical skills, he is also a gifted musician, composing local and gospel songs, often writing for church choirs, and always ready to sing and play music.

Perhaps one of the most striking symbols of Ma Wit’s self-reliance is his specially adapted car. Unlike conventional vehicles, this car is modified so that the accelerator and brake are near the steering wheel, allowing him to operate them with his hands. He discovered the existence of such vehicles by watching YouTube videos, realising that others with similar disabilities were driving them. Inspired, he sourced the necessary parts online and had someone custom-build the modifications. Since 2018, this car has given him an unparalleled sense of freedom. Before that, he navigated the roads on a three-wheeled scooty, but finding it uncomfortable, he ingeniously redesigned it to have only two wheels, perfectly suited to his needs. The first time he drove his car through the village, people were astonished, asking, “Are you not Ma Wit?” to which he proudly affirmed, “Yes, I am.”

He never received formal training for his diverse skills. His journey as a barber began years ago when few shops existed in his area. Parents would bring their children to him, armed with their own scissors, combs, and a jaiñkyrshah (a traditional Khasi female wear). Sometimes, he would even be working in his garden and offer haircuts right there. He found joy in it, practiced, and eventually became fluent in the craft.

For Ma Wit, it was more than just a job; it was “God’s opportunity, providing me with a work to sustain myself.” Similarly, his electrical repair skills grew from simply trying to fix things people brought to him, always doing whatever he could.

Ma Wit’s dedication to self-sufficiency stems from a deep desire to provide for himself and not rely on others for his basic needs. This independence fills him with immense contentment, a stark contrast to the dejection he once felt because of his disability. As the seventh of ten siblings, he is the only one in his family with a physical disability. While he admits to feeling ashamed in his younger years, time brought acceptance. He simply mbraced life as it is, transforming his challenges into stepping stones for resilience.

His artistic contributions extend to his songwriting. One of his powerful songs reflects on the new generation’s struggles, lamenting their lack of respect for elders, their interactions filled with cuss words, and how their negative attitudes affect those around them. He sings of parents losing track of their children’s whereabouts, actions, and speech, because respect has been “thrown down the drain.” He conveys a poignant message that God looks down on a world where worship has been forsaken for fleeting enjoyments and ruin. His lyrics serve as a potent call to self-reflection for the youth.

ALSO WATCH VIDEO IN KHASI:

Ma Wit’s story is a profound inspiration, not only for individuals facing similar physical challenges but for every one of us. In a world that often leans into dependence and overconsumption, where minor inconveniences like traffic jams or brief power outages cause significant distress, Ma Wit stands as a towering example. We, with our healthy bodies, sometimes view simple tasks like cooking or doing laundry as burdensome chores due to our ingrained reliance on convenience. We become frustrated by slow internet, a delayed delivery, or a smartphone glitch, forgetting the immense capabilities our own bodies possess. This constant craving for ease and instant gratification can inadvertently blind us to our own strengths and the simple joys of self-sufficiency.

Yet, Ma Wit, despite his disadvantages, thrives. He works tirelessly, cutting hair, repairing electronics, playing his guitar, and singing. His hands, though adapted for driving, are also skilled tools of his trade and instruments of his creativity. While he may not enjoy the conventional privileges many of us take for granted, the ease of unassisted movement, the unquestioning access to every service; he radiates happiness. This contentment stems not from what he possesses, but from a heart overflowing with gratitude towards his Creator.

His life serves as a powerful reminder: we should strive to turn our complaints into gratitude, shifting our focus from perceived lacks to the abundance that surrounds us. This shift in perspective allows us to truly appreciate the blessings we often overlook.

We must never take the health of our bodies for granted, nor become overly dependent on products and services to the point where they dictate our happiness or capacity. Sometimes we complain when we have to wash utensils or do our laundry, yet these very acts are blessings that remind us we have food to eat and clothes to wear. When your car isn’t working, or the traffic is heavy, consider that walking to the grocery store by foot is, in fact, a great privilege – a blessing many, like Ma Wit, remind us to cherish. Ma Wit’s life teaches us that true freedom and joy lie in embracing our circumstances with ingenuity, hard work, and an unwavering spirit of thankfulness, reminding us to cherish every single blessing, no matter how small or commonplace it may seem.

(Edited by Marba Rani)